13

Boscoreale. Villa della Pisanella. Villa rustica di Lucio Cecilio Giocondo alla

Pisanella.

Excavated 1895-1899.

The Treasure/Il Tesoro/Le trésor

Voir/See

Louvre - Trésor de Boscoreale RMN (Some but not all of the treasure items are shown on our pages. Use this link to see a more complete set of the items)

Casale A. Breve

storia degli scavi archeologici nel pagus Augustus Il Gazzettino Vesuviano 1979, pp. 6-10.

Casale A. La

favola delle cicogne da due boccali d'argento del Tesoro di Boscoreale:

Sylva Mala II 1981, p. 5 Centro

Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase

Casale A., D'Errico

A., Via e Vico Sanfelice (Dint' 'e Cappetella) L'Informa Comune, Boscoreale n.4 Dicembre 2006.

Gervais-Courtellemont,

J. 1895. Trésor de Boscoreale - Album de 33 planches INHA

Gervais-Courtellemont, J. 1895. Trésor

de Boscoreale – Avant restauration. Album de 17 planches INHA

Heron De Villefosse,

A. 1895. Le trésor d'argenterie de Bosco Reale Persee.fr

Heron De Villefosse,

A. 1899. Le Trésor de Boscoreale [article] Persee.fr

Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press

Casale A., Breve storia degli scavi

archeologici nel pagus Augustus. Il Gazzettino

Vesuviano 1979, pp. 6-10.

English (our approximate translation)

After these three excavations need to wait about a century, and precisely the 1876, for the pickaxes of the excavators to resume investigating our territory, looking for hidden treasures and easy gains.

In fact, in 1876 and precisely on November 9, Cav. Luigi Modestino Pulzella in his own fondo at the via Settetermini at Pisanella, in Boscoreale, during the excavation of the foundation for a boundary wall, met the rooms of the rustic quarter of the villa of Cecilio Giocondo or Tesoro di Boscoreale. The Cav. Pulzella, unfortunately for him, soon had to stop the archaeological exploration, because the Roman construction continued under the property of the neighbour, the lawyer Angelo Andrea De Prisco. The excavation work was suspended, and De Prisco did not continue the excavation neither then nor in the following years.

It was his son Vincenzo, who will also become a member of Parliament, who was to undertake the excavation of the villa in the years 1894-99.

From the volume "Herculaneum and Pompeii" of the Austrian count Egon Caesar Corti, we come to know the history of the discovery of the villa of Cecilio Giocondo and the Silver Treasure.

Let us now talk about Corti: "... on 10 September 1894 (Vincenzo De Prisco) he decided to undertake excavations on his own, which were conducted with extreme skill and brought to light the complex of a large country house with living rooms, baths, warehouses for the manufacture and storage of wine and oil and even a room for pressing ". “In that isolated building, which remained intact for 1800 years, everything was in its place: furnishings and furniture, bronze bathtubs decorated with masks in the shape of lion heads, seemed to have remained there ready for use. In a large chest there were fifty keys and silver tableware; in the kitchen the skeleton of the dead dog on a chain; in the stable the bones of several tethered horses, one of which had managed to wriggle out and escape. In the torcularium the first three human skeletons came to light, including that of a woman, probably the mistress of the house, who wore splendid gold earrings with topazes. Everything in that house, the arrangement of the objects and the position of the dead, allowed me to reconstruct exactly the last hours that had been lived there.

But the most sensational discovery took place at Easter, on April 13, 1895. On the eve of the public holiday, the workers had already left the works, and on the spot there were only a few men to complete the clearing of two tunnels that entered the wine cella, when one of them, , when one of them, a certain Michele, pushed to the bottom of the narrow corridor, returned saying that the place was saturated with poisonous fumes and he couldn't breathe. Of course no one wanted to expose himself to that danger and the overseer gave orders to suspend work for the time being. Everyone left, but Michele, leaving the others, ran instead to the landowner. "Sir - he said - the wine cellar is completely empty, but on the floor I saw a dead man in the midst of wonderful silver vases, bracelets, earrings, rings, a double gold chain and a sack full of pure gold coins”.

The master ordered him not to open his mouth and persuaded him to stay with him that night. As darkness fell, the two, armed with lanterns and baskets, descended underground and remained breathless in front of a true profusion of precious objects, scattered around a skeleton lying on the ground, on the face and on the hands. In addition to many beautifully crafted silver vases, there was a leather bag from the impression still visible, which contained the beauty of a thousand gold coins that bore the effigy of all the emperors succeeding Augustus to Domitian, until 76 A.D. Some were of the time of Galba, Otho and Vitellius, so very rare, because these three monarchs had reigned only a few months each [The year of the four Emperors 69 A.D.].

The pieces of the Augustan and Tiberian age were more eroded, but those of the Neronian era, 575 in all, were practically new, freshly minted. The gold objects were naturally unchanged, while the silver vases were covered with a thick dark patina.

The two lucky ones packed their baskets and hurried to transport the treasure to a safe hiding place, promising to sell it at an advantageous price abroad, in spite of the Italian laws forbidding the export of antique objects. Michele was rewarded properly and, after some time, received a second conspicuous gratification, as a reward for his silence. He was so happy that he went to the tavern and got drunk. Alas, in the fumes of wine the tongue melted and he told the story of the discovery step by step. The news spread across the area with the speed of lightning and came to the ears of the authorities who immediately began an investigation. But the treasure had already crossed the border: since May, the 117 pieces of silverware and the sack with the precious coins had been in Paris. First they were offered to the Louvre museum for the total sum of half a million francs, then, the museum having made a counter-offer of 250,000 francs, payable in five annual instalments, the negotiations were interrupted and the objects were instead purchased by Baron Edmond de Rothschild, who kept some of them for his private collection (The cups of Tiberius and Augustus), and donated 109 pieces of silverware and all the coins to the Louvre museum.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Silver Treasure. Silver mug

with skeletons, Louvre Museum, Paris.

See Casale A., Breve storia degli scavi archeologici nel pagus Augustus. Il Gazzettino Vesuviano 1979, pp. 6-10, Fig. 2.

Among the silver vessels found in Boscoreale, there are two particularly interesting, called the pots of skeletons that, with the representation of death, want to urge men to enjoy life before it is too late. The embossing of one of the cups depict the tragic poet Sophocles, the Platonic poet and philosopher Mosco [Moschus?] and the Epicurean Zeno; The other has skeletons of Euripides, Menander and the cynical poet Monimus symbolize poetry, music and philosophy, while the anonymous skeletons depict men in general.

Mosco and Menander, poets who revealed to their contemporaries the secret joys of love, hold female masks that represent the heroines of their comedies, and the Greek legends traced in punctuations explain the meaning of the allegory.

The bowls, produced at the time of Alexander the Great under the banner of Hellenism, attest to the Epicurean conception of the time. "Enjoy as long as you live -says one of the writings In Greek- because tomorrow is uncertain. Life is a comedy, enjoyment the supreme good, voluptuousness is the most precious treasure: be happy, as long as you are alive." The skeletons engraved on the silver bowls destined to contain delicious wines, recalling in the eyes of the delighted guests the vision of death, the warning: "Look at those gloomy bones, drink and enjoy as long as you can: one day you too will be like this."

The sale abroad of the Boscoreale treasure was the subject of questions to the Italian Parliament, but by now the objects had passed in the hands of third parties and there was nothing more left to do ".

The De Prisco were, we can say, a family of

"archaeologists", because not only Vincenzo carried out excavations

authorized by the State, between the end of the 1800s and the beginnings of

1900s, but also his brother Ferruccio, in the fondo owned by Acunzo at the

railway station of the state of Boscoreale, where a rustic villa was found with

the walls simply plastered, belonging to a modest family of farmers. This excavation was carried out in 1903.

The enormous amount of objects found in the excavation of the Villa of the Treasure led the Hon. Vincenzo De Prisco to continue the archaeological exploration in neighbouring fondo’s to his and his other properties in Scafati and Giuliano. He found other rustic villas:

In the fondo of Ippolito Zurlo in the contrada Giuliano of Boscoreale in the years 1895-97;

In the property of Vito Antonio Cirillo, at Piazza Mercato in

Boscoreale, in 1897;

In the fondo

Acanfora in Contrada Spinelli in Pompeii, known as "Villa of Domitius Auctus". In 1899;

In his fondo in Contrada Crapolla (Lazzaretto) in Scafati in early 1900;

In the Fondo De Martino in the contrada Pisanella of Boscoreale, known as Villa di Asellius, in the years 1903-1904.

But the most important discovery of De Prisco, beyond that of the Villa of the Silver Treasure, remains the villa of Fannio Sinistore in the fondo Vano, in via Grotta a Boscoreale, Very interesting for the megalographic frescoes (life-size) found therein, similar to those of Villa of the mysteries.

That villa unlike that of the Treasure, had scarcely developed the rustic quarter; This was a noble residence, with large rooms frescoed in the so-called Pompeian style, owned by the gens Fannia.

See Casale A., Breve

storia degli scavi archeologici nel pagus Augustus. Il Gazzettino Vesuviano

1979, pp. 6-10.

See https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/pdf/breve%20storia%20pagus%20augustus.pdf

Courtesy of Centro

Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase. Our

thanks to Angelandrea Casale.

See Casale A.,

D'Errico A., Via e Vico Sanfelice (Dint' 'e Cappetella) 5 puntata, in L'Informa Comune,

Boscoreale n.4 Dicembre 2006.

See https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/informacomune/5apuntata.pdf

Courtesy of Centro

Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase. Our

thanks to Angelandrea Casale.

Italiano

Dopo questi

tre scavi bisogno aspettare circa un secolo, e precisamente il 1876, affinché

il piccone degli scavatori riprendo ad indagare nel nostro territorio, alla

ricerca di tesori nascosti e di facili guadagni.

Infatti

proprio nel 1876 e precisamente Il 9 novembre il cav. Luigi Modestino Pulzella

incontrò nel proprio fondo alla via Settetermini alla Pisanella, a Boscoreale,

durante lo scavo delle fondamento per un muro di cinta, delle stanze, che poi

si scoprirà essere il quartiere rustico della villa di Cecilio Giocondo o del

Tesoro di Boscoreale. Il cav. Pulzella, sfortunatamente per lui, dopo poco

dovette fermare l'esplorazione archeologico, perché la costruzione romano

continuavo sotto la proprietà del vicino, l'avv. Angelo Andrea De Prisco. I

lavori di scavo furono sospesi, ed il De Prisco non proseguì lo scavo né allora

né negli anni successivi.

Fu suo figlio

Vincenzo, che diventerà anche Deputato al Parlamento, ad intraprendere lo scavo

della villa negli anni 1894-99.

Dal volume “Ercolano

e Pompei " del conte austriaco Egon Caesar Corti, veniamo a conoscere la

storia del rinvenimento della villa di Cecilio Giocondo e del tesoro delle

argenterie.

Facciamo

parlare ora il Corti: “ ...il 10 settembre 1894

(Vincenzo De Prisco) decise di intraprendere per conto suo degli scavi, che

vennero condotti con estrema perizia e misero alla luce il complesso di uno grande

casa di campagna con stanze di soggiorno, bagni, depositi per la fabbricazione

e la conservazione del vino e dell'olio e persino un locale per la pigiatura”.

“In quell'edificio isolato, rimasto intatto per 1800 anni, tutto era al suo

posto: suppellettili e mobili, vasche da bagno in bronzo ornate di mascheroni

in formo di protomi leonine, sembravano essere rimasti lì pronti per l'uso. In

un grosso cofano c'erano cinquanta chiavi e del vasellame d'argento; nella

cucina lo scheletro del cane morto alla catena; nella stalla le ossa di

parecchi cavalli legati, di cui uno ero riuscito a divincolarsi e a fuggire.

Nel cortile dei torchi vennero in luce i primi tre scheletri umani, fra cui

quello di una donna, probabilmente la padrona di casa, che portavo splendidi

orecchini in oro e topazi. Tutto in quella casa, la disposizione degli oggetti

e posizione del morti, permettevo di ricostruire

esattamente le ultime ore che vi erano state vissute.

Ma la scoperta

più sensazionale ebbe luogo a Pasqua, il 13 aprile del 1895. Alla vigilia del

giorno festivo, gli operai già avevano lasciato i lavori, e sul posto erano

rimasti solo alcuni uomini per ultimare lo sgombero di due cunicoli che immettevano

nella cella vinario, quando uno di essi, un certo Michele, spintosi in fondo allo

stretto corridoio, ritornò dicendo che il locale ero saturo di esalazioni

velenose e non si potevo respirare. Naturalmente nessuno ebbe voglia di esporsi

a quel pericolo e il sorvegliante diede senz'altro ordine di sospendere per il

momento il lavoro. Tutti se ne andarono, ma Michele, appartandosi dagli altri,

corse invece dal proprietario del fondo. “Signore - gli disse - , il cellaio del vino è completamente vuoto, ma sul

pavimento ho visto un morto in mezzo a dei meravigliosi vasi d'argento, bracciali,

orecchini, anelli, uno doppio catena d'oro e un sacco zeppo di monete pure

d'oro”.

Il padrone gli

ordinò di non aprir bocca e lo persuase a rimanere con lui quella notte. Appeno

cadute le tenebre, i due, muniti di lanterne e di ceste, scesero nel

sotterraneo e rimasero col fiato mozzo dinanzi a una vera profusione di oggetti

preziosi, sparpagliati intorno ad uno scheletro disteso per terra, sulla faccia

e sulle mani. Oltre a moltissimi vasi d'argento splendidamente lavorati, c'ero

un sacco di cuoio dall'iscrizione ancora visibile, il quale contenevo la

bellezza di mille nummi d'oro che recavano l'effige di tutti gli Imperatori

susseguitisi da Augusto a Domiziano, fino al 76 d.C. Alcuni erano del tempo di Galba,

Otone e Vitellio, quindi rarissimi, perché questi tre monarchi non avevano

regnato che pochi mesi ciascuno.

I pezzi

dell'epoca augustea e tiberiana erano più consumati, ma quelli dell'epoca

neroniana, 575 in tutto, erano praticamente nuovi, fiori di conio. Gli oggetti

d'oro erano naturalmente inalterati, mentre i vasi d'argento si erano ricoperti

di una spessa patina scura.

I due

fortunati inzepparono le ceste e si affrettarono a trasportare il tesoro in un

nascondiglio sicuro, ripromettendosi di venderlo a un prezzo vantaggioso

all'estero, in barba alle leggi italiane che vietavano l'esportazione di

oggetti antichi. Michele fu ricompensato a dovere e, dopo qualche tempo,

ricevette una seconda vistosa gratificazione, come premio al suo silenzio. Ne

fu cosi contento, che andò all'osteria e si ubriacò. Ahimè!,

nei fumi del vino la lingua gli si sciolse ed egli raccontò per filo e per

segno la bravata della scoperta. La notizia si sparse nella zona con la

rapidità del lampo ed arrivò alle orecchie delle autorità che subito iniziarono

un'inchiesta. Ma il tesoro aveva ormai passato la frontiera: sin dal mese di maggio,

i 117 pezzi di argenteria e il sacco con le preziose monete si trovavano a

Parigi. Dapprima furono offerti al museo del Louvre per la somma complessiva di

mezzo milione di franchi, poi, avendo il museo fatto uno contro-offerta di

250.000 franchi, pagabili in cinque rate annue, le trattative furono interrotte

e gli oggetti furono invece acquistati dal barone Edmondo Rothschild, che ne

tenne alcuni per la sua collezione privata (le tazze di Tiberio e di Augusto),

e legò 109 pezzi di argenteria e la totalità delle monete al museo del Louvre.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Tesoro delle argenterie di Boscoreale. tazza

d'argento con raffigurazioni di scheletri, Museo del Louvre, Parigi.

Vedi Casale A., Breve

storia degli scavi archeologici nel pagus Augustus. Il Gazzettino Vesuviano

1979, pp. 6-10, Fig. 2.

Fra i vasi

d'argento ritrovati a Boscoreale, ve ne sono due particolarmente interessanti,

chiamati i Vasi degli Scheletri che, con la rappresentazione della morte,

vogliono esortare gli uomini a godere della vita prima che sia troppo tardi. Le

cesellature di una delle coppe raffigurano il poeta tragico Sofocle, il poeta e

filosofo platonico Mosco e l'epicureo Zenone; quelle dell'altra gli scheletri

di Euripide, di Menandro e del poeta cinico Monimo.

Essi simboleggiano la poesia, la musico e la filosofia, mentre gli altri

scheletri, anonimi, raffigurano gli uomini in genere.

Mosco e

Menandro, poeti che rivelarono ai loro contemporanei le gioie segrete dell'amore,

tengono in mano delle maschere femminili che rappresentano le eroine delle loro

commedie, e le leggende greche tracciate a punteggiature spiegano il

significato dell'allegoria.

Le coppe,

fabbricate al tempo di Alessandro Magno sotto il segno dell'ellenismo,

attestano la concezione epicurea dell'epoca. ”Godi finché

vivi - dice uno delle scritte In greco -, poiché il domani è incerto. La vita è

una commedia, il godimento il bene supremo, la voluttà il tesoro più prezioso: sii

lieto, finché sei in vita”. Gli scheletri incisi sulle coppe d'argento

destinate a contenere vini prelibati, richiamando agli occhi dei lieti

convitati la visione della morte, il ammonivano: “Guarda quelle lugubri ossa,

bevi e godi finché puoi: un giorno anche tu sarai cosi”.

La vendita

all'estero del tesoro di Boscoreale formò oggetti di una interpellanza al

Parlamento italiano, ma ormai gli oggetti erano passati nelle mani di terzi e

non c'ero più nulla da fare”.

I De Prisco

furono, possiamo dire, una famiglia «d'archeologi », perché

non solo Vincenzo effettuò scavi autorizzati dallo Stato, tra la fine dell'800

e gli inizi del '900, ma anche suo fratello Ferruccio, nel fondo di proprietà

d'Acunzo presso la Stazione delle Ferrovie dello Stato di Boscoreale, dove si rinvenne

una villa rustica dalle pareti semplicemente intonacate, appartenuta ad una

modesta famiglia di agricoltori. Questo scavo fu eseguito nel 1903.

L'enorme

quantità di oggetti ritrovati nello scavo della villa del Tesoro, indussero

l'on. Vincenzo De Prisco a proseguire l'esplorazione archeologica in fondi

limitrofi al suo ed in altre sue proprietà a Scafati ed alla Giuliano. Egli

rinvenne cosi altre ville rustiche:

nel fondo di

Ippolito Zurlo alla contr. Giuliano di Boscoreale negli anni 1895-97;

nella

proprietà di Vito Antonio Cirillo, presso piazza Mercato a Boscoreale, nel

1897;

nel fondo Acanfora

in contr. Spinelli a Pompei, conosciuto come « villa

di Domiti Auctì ». nel 1899;

nel suo fondo

in contrada Crapolla (Lazzaretto) a Scafati agli inizi del 1900;

nel fondo De Martino

alla contr Pisanella di Boscoreale, conosciuto come villa di Aselli negli anni

1903-1904.

Ma il più

importante rinvenimento del De Prisco, oltre quella della villa del Tesoro

delle argenterie, resta la villa di Fannio Sinistore nel fondo Vana, in via

Grotta a Boscoreale, interessantissima per gli affreschi megalografici

[a grandezza naturale) simili a quelli di villa dei Misteri, ivi rinvenuti.

La villa a differenza di quella del Tesoro, aveva poco sviluppato Il quartiere

rustico; si tratto qui di una residenza nobile, con grandi camere affrescate

nel cosiddetto Il stile pompeiano, di proprietà della gens Fannia [fig. 3).

Ved.

https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/pdf/breve%20storia%20pagus%20augustus.pdf

Per gentile concessione di Centro Studi

Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase. I nostri ringraziamenti ad

Angelandrea Casale.

Ved. Casale A., D'Errico A., Via e Vico

Sanfelice (Dint' 'e Cappetella)

5 puntata, in L'Informa Comune, Boscoreale n.4 Dicembre 2006.

Ved. https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/informacomune/5apuntata.pdf

Per gentile

concessione di Centro Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale,

Boscotrecase e Trecase. I nostri ringraziamenti ad Angelandrea

Casale.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale treasure on show in the Louvre.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Thierry Ollivier.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver treasure, front view.

Now in the Louvre.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver treasure, side view.

Now in the Louvre.

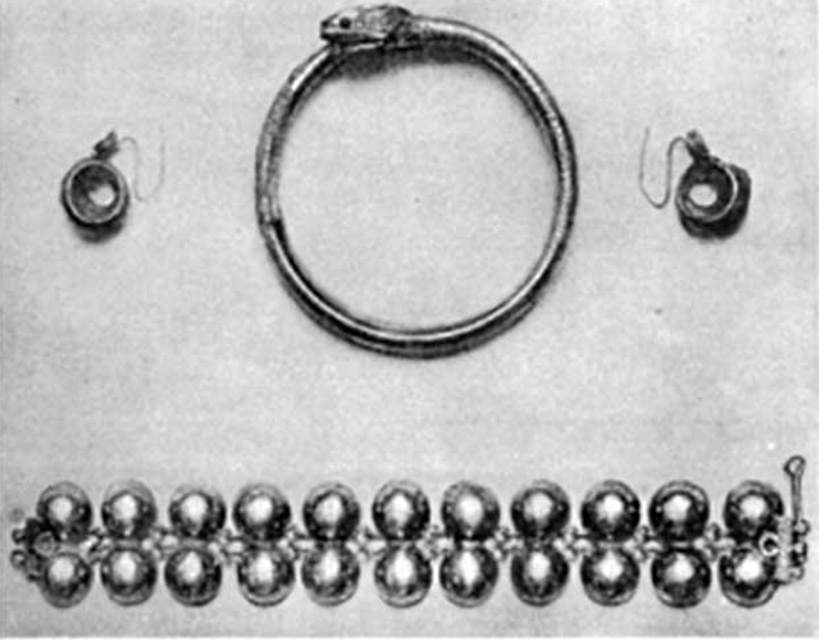

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. A part of the Boscoreale treasure.

See Elisabetta Cardone. Boscoreale: tesori archeologici e villa della Pisanella. https://www.vesuviolive.it/

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Pair of gold earrings.

Paire de

boucles d'oreille.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ408 and BJ409.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Tony Querrec.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Pair of gold bracelets. Each bracelet consists of eleven pairs of hollow half-spheres separated by a twist. Closing with a clasp.

Paire de

bracelets. Chaque bracelet est formé de onze paires de demi-sphères creuses

séparées par une torsade. Fermeture à clavette.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ990 BJ991.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé

Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Gold snake bracelet, coiled and with scales decoration.

Trésor de Boscoreale. Bracelet de serpent en or, enroulé avec décor

d'écailles.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ976 .

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Les frères

Chuzeville.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Pair of gold coiled snake bracelets.

Trésor de

Boscoreale. Paire de bracelets de serpent enroulés, en or.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ976 and BJ977.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Les frères

Chuzeville.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Gold double chain. Eight-spoke wheels allowed the chain to be fixed on your shoulders.

Chaîne-baudrier

(double chaîne). Des rouelles à huit rais devaient permettre de fixer la chaîne

sur les épaules.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ495. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski.

See De Villefosse

H., 1899. L'argenterie et bijoux d'or du trésor de Boscoreale description

des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre: Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec

Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, p. 264, fig. 56.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. 1899. Gold jewellery. Bijoux en or.

See

De Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre: Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec

Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, p. 267, fig. 57.

See Rivista di

Studi Pompeiani, 22, 2011, p. 43.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver hand mirror.

In the centre, in a medallion: bust of

Bacchante.

According to De Villefosse, Mirror adorned with the bust of Ariadne and bearing the signature of the engraver M. Domitius Polygnos, with the indication of the weight of the piece.

Miroir à

manche. Au centre, dans un médaillon : buste de Bacchante.

Selon De

Villefosse, Miroir orné du buste d'Ariane et portant la signature du ciseleur

M. Domitius Polygnos, avec l'indication du poids de la pièce.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2158.

See De Villefosse

H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale description

des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XIX.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Hand mirror: in the centre in a medallion: Leda and the swan. Silver with repoussé decoration.

Miroir à

manche : Au centre, dans un médaillon : Léda et le cygne. Argent avec décoration repoussé.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2159.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver 18. Cup with emblema. Bust of

an elderly man. Owners name engraved in Latin: Max (ima).

Coupe à

emblema. Buste d'homme âgé. Nom propre gravé en latin : Max(ima).

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1970.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Cup with emblema. Bust of elderly man.

Coupe à

emblema. Buste d'homme âgé.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1970.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. The emblema (decorative centre-piece) of a silver dish: bust of a woman, inscribed: "Maxima's".

The dish was one of a pair, the other representing an elderly man.

According to De Villefosse, this phiale had a pendant of the same shape and the same dimension, decorated with a woman's head. Violently torn, in antiquity, from the washer which formed the bottom of the emblema, as evidenced by the tears in the silver leaf at its base, this head was collected separately in another part of the house and sold before the arrival of the treasure in Paris. After belonging to Count Michel Tyszkiewicz, it entered the collections of the British Museum; the phiale was not found. This female head has exactly the same shape and dimensions as the male head.

L'emblème

(pièce centrale décorative) d'un plat d'argent: buste

d'une femme, inscrit: "Maxima's".

Le plat était

l'un d'une paire, l'autre représentant un homme âgé.

Selon De

Villefosse, cette phiale avait un pendant de même forme et de même dimension,

orné d'une tête de femme. Violemment arrachée, dans l'antiquité, de la rondelle

qui constituait le fond de l'emblema, ainsi que l'attestent les déchirures de

la feuille d'argent à sa base, cette tête a été recueillie séparément dans une

autre partie de l'habitation et mise dans le commerce avant l'arrivée du trésor

à Paris. Après avoir appartenu au comte Michel Tyszkiewicz,

elle est entrée dans les collections du Musée britannique;

la phiale n'a pas été retrouvée. Cette tête de femme a exactement la même forme

et les mêmes dimensions que la tête d'homme.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre: Monuments

et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, p. 45-6, figs. 8-9.

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum. Inventory number BM 1895,0622.1. Use subject to CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. A club handled mirror.

Handle attached to the mirror by a lion's skin. Polished disc.

Miroir à

manche en forme de massue.

Manche

rattaché au miroir par une peau de lion. Disque

poli.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2160.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Hervé

Lewandowski.

![Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Cup without foot.

Decorated with a female bust: Cleopatra? or her daughter [Cleopatra Selene II] ? Allegory of Africa? or Alexandria? covered with an elephant's body and accompanied by a profusion of symbols - Latin inscription: measure of weight.

Coupe sans pied.

Décorée d'un buste féminin : Cléopâtre ? ou sa fille [Cléopâtre Séléné II] ? allégorie de l'Afrique ? ou d'Alexandrie ? recouvert d'une dépouille d'éléphant et accompagné d'une profusion de symboles - Inscription latine : mesure de poids.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1969.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.](Villa_013%20Boscoreale%20Villa%20della%20Pisanella%20p4_files/image020.jpg)

Villa

della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Cup without foot.

Decorated with a female bust: Cleopatra? or her daughter [Cleopatra Selene II] ? Allegory of Africa? or Alexandria? covered with an elephant's body and accompanied by a profusion of symbols - Latin inscription: measure of weight.

Coupe sans

pied.

Décorée d'un

buste féminin : Cléopâtre ? ou sa fille [Cléopâtre Séléné II]

? allégorie de l'Afrique ? ou

d'Alexandrie ? recouvert d'une dépouille d'éléphant et accompagné d'une

profusion de symboles - Inscription latine : mesure de poids.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1969.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Large phial adorned with

the bust of Africa-Panthea.

Grande phiale ornée du buste de l'Afrique-Panthée.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. I.

See also Mau, A., 1902, translated by Kelsey F. W. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: Macmillan, fig. 187 p. 367.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. View of some of the Boscoreale Treasure.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Les frères Chuzeville.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. View of some of the Boscoreale Treasure with, in addition, the emblema cup (BJ1970).

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale treasure: ewers, cups with skeletons, cup.

Louvre inventory numbers BJ1898, BJ1969, BJ1923, BJ1924, BJ1899.

Trésor de

Boscoreale : aiguières, gobelets aux squelettes, coupe.

Numéros

d'inventaire du Louvre BJ1898, BJ1969, BJ1923, BJ1924, BJ1899.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

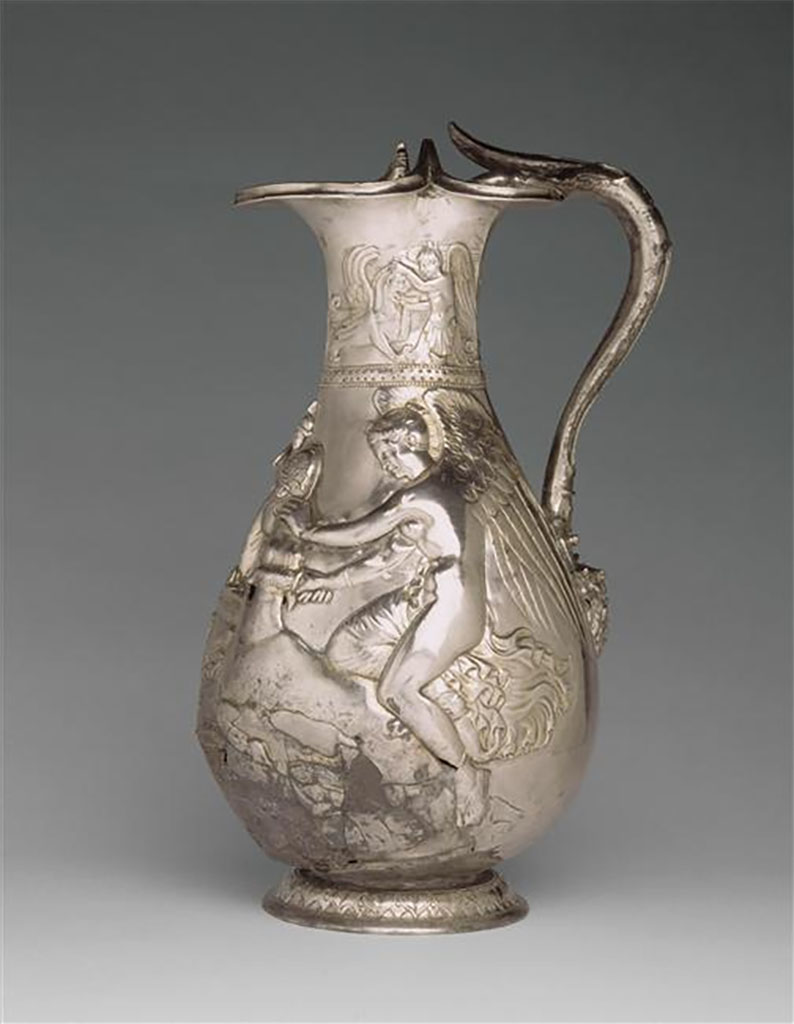

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Two ewers, silver wine vases with repousse decoration and traces of gilding.

Height about 25

cm.

Deux aiguières du trésor de Boscoreale - Vase à vin en argent décors repoussé, traces de dorure. Hauteur environ 25 cm.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ 1898: BJ1899.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Front: Ewer, silver wine vase with repousse decoration and traces of gilding. Height about 25 cm. Side 1.

On the neck: a winged genius give water to a griffin. On the body: one victory sacrifices a deer: In the centre is an altar bearing the palladium.

Avant : Aiguière

du trésor de Boscoreale - Vase à vin en argent décors repoussé, traces de

dorure. Hauteur environ 25 cm. Côté 1.

Sur le col : un génie ailé abreuvant un

griffon. Sur la panse: une victoire sacrifie un cerf.

Au centre un autel portant le palladion.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ 1898.

On the neck: a winged genius gives water to a griffin. On the body: one victory on a ram, offers incense and an olive branch. Handle terminated at bottom with a head of Silenus crowned with ivy.

Sur le col : un génie ailé abreuvant un

griffon. Sur la panse: une victoire sur un bélier,

offre de l'encens et un rameau d'olivier. Anse terminé en bas par une tête de

Silène couronnée de lierre.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ 1898.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Ewer, silver wine vase with repousse decoration and traces of gilding.

Height about 25 cm. In the centre an altar bearing the Palladium.

Sur le col : deux génies ailés abreuvant des griffons. Sur la panse : une

victoire sacrifie un cerf, l'autre sur un bélier, offre de l'encens et un rameau

d'olivier : Au centre un autel portant le Palladion.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Ewer from the treasure of Boscoreale - Silver wine vase with repousse decorations, traces of gilding, late 1st century AD - Height about 25 cm. Side 1.

On the collar a winged genius gives water to a griffin. On the body one of two Victories sacrificing a bull on either side of an altar bearing the Palladium.

Aiguière du

trésor de Boscoreale - Vase à vin en argent décors repoussé, traces de dorure,

fin du Ier siècle ap. J.C. - Hauteur environ 25 cm. Côté 1.

Sur le col un

génie ailé abreuvant un griffon. Sur la panse l’un des deux Victoires

sacrifiant un taureau de part et d'autre d'un autel portant le Palladion.

Now in the Louvre, Inventory number BJ 1899.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Ewer from the treasure of Boscoreale - Silver wine vase with repousse decorations, traces of gilding, late 1st century AD - Height about 25 cm. Side 2.

On the collar a winged genius gives water to a griffin. On the body one of two Victories sacrificing a bull on either side of an altar bearing the Palladium.

Aiguière du

trésor de Boscoreale - Vase à vin en argent décors repoussé, traces de dorure,

fin du Ier siècle ap. J.C. - Hauteur environ 25 cm. Côté 2.

Sur le col un génie ailé abreuvant un griffon. Sur la panse l’un des deux

Victoires sacrifiant un taureau de part et d'autre d'un autel portant le Palladion.

Now in the Louvre, Inventory number BJ 1899.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. View of some of the cups from the Boscoreale Treasure.

Vue de certaines des tasses du trésor de

Boscoreale.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. View of some of the goblets, cups, plates and ewers from the Boscoreale Treasure.

Vue de

quelques-unes des gobelets, tasses, assiettes et des aiguilles du trésor

Boscoreale.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. One of two skeleton cups. Under garlands of roses: four scenes. Dotted inscriptions giving meaning accompanied by epicurean maxims. Skeletons representing renowned authors: Euripides, Sophocles, Menander, Moschion, and philosophers: Zeno, Epicure, Monime of Athens, Demetrius of Phalerum accompanied by explicit sentences.

Une des deux gobelets

aux squelettes. Sous des guirlandes de roses : quatre scènes.

Inscriptions en pointillé donnant la signification accompagnés

de maximes épicuriennes. Les squelettes représentant des auteurs de renom : Euridipe, Sophocle, Ménandre, Moschion, et des philosophes

: Zénon, Epicure, Monime d'Athènes, Démétrios de Phalère accompagnés de

sentences explicites.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1923 [and BJ1924].

![Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Second of two skeleton cups. Under garlands of roses: four scenes. Dotted inscriptions giving meaning accompanied by epicurean maxims. Skeletons representing renowned authors: Euripides, Sophocles, Menander, Moschion, and philosophers: Zeno, Epicure, Monime of Athens, Demetrius of Phalerum accompanied by explicit sentences.

Deuxième de deux gobelets aux squelettes. Sous des guirlandes de roses : quatre scènes. Inscriptions en pointillé donnant la signification accompagnés de maximes épicuriennes. Les squelettes représentant des auteurs de renom : Euridipe, Sophocle, Ménandre, Moschion, et des philosophes : Zénon, Epicure, Monime d'Athènes, Démétrois de Phalère accompagnés de sentences explicites.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1924 [and BJ1923].](Villa_013%20Boscoreale%20Villa%20della%20Pisanella%20p4_files/image034.jpg)

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Second of two skeleton cups. Under garlands of roses: four scenes. Dotted inscriptions giving meaning accompanied by epicurean maxims. Skeletons representing renowned authors: Euripides, Sophocles, Menander, Moschion, and philosophers: Zeno, Epicure, Monime of Athens, Demetrius of Phalerum accompanied by explicit sentences.

Deuxième de

deux gobelets aux

squelettes. Sous des guirlandes de roses : quatre scènes. Inscriptions en

pointillé donnant la signification accompagnés de

maximes épicuriennes. Les squelettes représentant des auteurs de renom : Euridipe, Sophocle, Ménandre, Moschion, et des philosophes

: Zénon, Epicure, Monime d'Athènes, Démétrios de Phalère accompagnés de

sentences explicites.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1924 [and BJ1923].

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Goblet with one handle, decorated with skeletons and topped with garlands of roses.

Gobelet à

une anse, décoré de squelettes et surmonté de guirlandes de roses.

Voir/See Gervais-Courtellemont, Jules, 1895. Trésor

de Boscoreale : Album de 33 planches. L'Institut national d'histoire

de l'art (INHA), Pl. 30.

Document placé

sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Goblet with one handle, decorated with skeletons and topped with garlands of roses.

Gobelet à

une anse, décoré de squelettes et surmonté de guirlandes de roses.

Voir/See Gervais-Courtellemont,

Jules, 1895. Trésor de Boscoreale : Album de 33 planches.

L'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), Pl. 31.

Document placé

sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. 3 views of a goblet with one handle, decorated with skeletons and topped with garlands of roses.

3 vues d’un

gobelet à une anse, décoré de squelettes et surmonté de guirlandes de roses.

Document placé sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Various items in the Boscoreale Silver Treasure.

Divers

objets dans le trésor d'argent Boscoreale.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Bowl decorated with hospitality gifts, with the name of

Sabeinos.

Side 1. Hare, mushrooms, pomegranates, thrushes, basket.

Side 2. Suckling pig, turtle, wicker basket, knife sheath, pot.

Ecuelle

décorée de présents d'hospitalité, avec le nom de Sabeinos.

Côté 1. Lièvre, champignons, grenades, grives,

panier.

Côté 2. Cochon de lait, tortue, corbeille

d'osier, gaine à couteaux, marmite.

Voir/See Gervais-Courtellemont,

Jules, 1895. Trésor de Boscoreale : Album de 17 planches.

L'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), Pl. 15.

Document placé

sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XVI.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Bowl decorated with hospitality gifts, with the name of Sabeinos.

Side 1. Beets, wild boar, amphora, knife, table laden with silverware.

Side 2. Shrimps, goose, dead hare, thrushes, basket of grapes.

Ecuelle décorée

de présents d'hospitalité, avec le nom de Sabeinos.

Côté 1. Raves,

sanglier, amphore, couteau, table chargée d'argenterie.

Côté 2. Crevettes,

oie, lièvre mort, grives, hottée de raisins.

Voir/See Gervais-Courtellemont,

Jules, 1895. Trésor de Boscoreale : Album de 17 planches.

L'Institut national d'histoire de l'art (INHA), Pl. 16.

Document placé

sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

Voir/See De Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor

de Boscoreale description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XV.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Part of the Silver Treasure. On the silver tray are three silver salt cellars with tripod feet.

Sur le

plateau d'argent sont trois salières

d'argent avec des pieds trépieds.

Louvre inventory numbers BJ1953 (Plat), BJ1998, BJ1999, BJ2000 (salières).

Guilloche decoration, tongues and friezes of palmettes and flowers. Owners name engraved in Latin: Pamphilus, imperial freedman.

Trépied miniature avec pied zoomorphe supportant

une salière. Salière : décor de guillochis,

languettes et frise de palmettes et de fleurs.

Nom propre gravé en latin : Pamphilus, affranchi

impérial.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2000.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) /

Stéphane Maréchalle.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Silver. Miniature tripod with zoomorphic foot supporting a salt cellar.

Guilloche decoration, tongues and

friezes of palmettes and flowers. Owners name engraved

in Latin: Pamphilus, imperial freedman.

Trépied

miniature avec pied zoomorphe supportant une salière. Salière : décor de

guillochis, languettes et frise de palmettes et de fleurs.

Nom propre

gravé en latin : Pamphilus, affranchi impérial.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1999.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Pair of cantharus decorated with plane tree leaves.

Paire de

canthares à décor de feuilles de platane.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1909 and BJ1910.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Detail of one of a pair of cantharus decorated with plane tree leaves.

Détail de

l'un d'une paire de

canthares à décor de feuilles de platane.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Pair of scyphi decorated with Dionysian scenes, face with child, donkey and elephant.

Paire de skypoï à décor de scènes dionysiaque, face avec enfant, âne et éléphant .

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1911 and BJ1912.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale Treasure. Pair of scyphi decorated with Dionysian scenes, face with child and panther and lion.

Paire de skypoï à décor de scènes dionysiaques, face avec enfant et

panthère et lion .

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1911 and BJ1912.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. One of a pair of silver Cantharus decorated with

floral scrolls and animal fights; eagle skinning a hare; dogs attacking a

deer.

Vase à mêler

le vin, orné de rinceaux avec poursuites d'animaux : aigle dépeçant un lièvre; chiens forçant un cerf.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1907.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. IX.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Boscoreale silver. Detail of silver Cantharus decorated with floral scrolls and animal fights.

Détail de Canthares argenté à décor de rinceaux

floraux et combats d'animaux

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1907.

Voir/See De Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor

de Boscoreale description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. IX.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. At

the back is the reverse side of the silver Cantharus decorated with

floral scrolls and animal fights.

A l'arrière se trouve l'inverse du Cantharus

argenté à décor de rinceaux floraux et combats

d'animaux.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1907.

Voir/See De Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor

de Boscoreale description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. X.

At the front is

one of a pair of cantharus, with scenes with storks.

Two scenes unfold around the storks' nest: the parents bring prey back to their young and are challenged by an intruder

À l'avant est

l'un d'une paire de cantharus, avec des scènes avec des cigognes.

Deux tableaux

se déroulent autour du nid des cigognes : les parents rapportent à leurs petits

des proies qui leur sont disputées par un intrus

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1904.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre: Monuments

et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XIII.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Side of the silver Cantharus decorated with

floral scrolls and animal fights; Stork flapping wings in front of a snake;

a lion and a bull fighting.

Cote du

Cantharus argenté à décor de rinceaux floraux et combats d'animaux ;

Cigogne battant des ailes devant un serpent; combat

d'un lion et d'un taureau.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1908.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. X.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Reverse side of the silver Cantharus decorated with

floral scrolls and animal fights.

Côté inverse

du Cantharus argenté à décor de rinceaux floraux et combats d'animaux.

Photo © RMN-Grand

Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ1908.

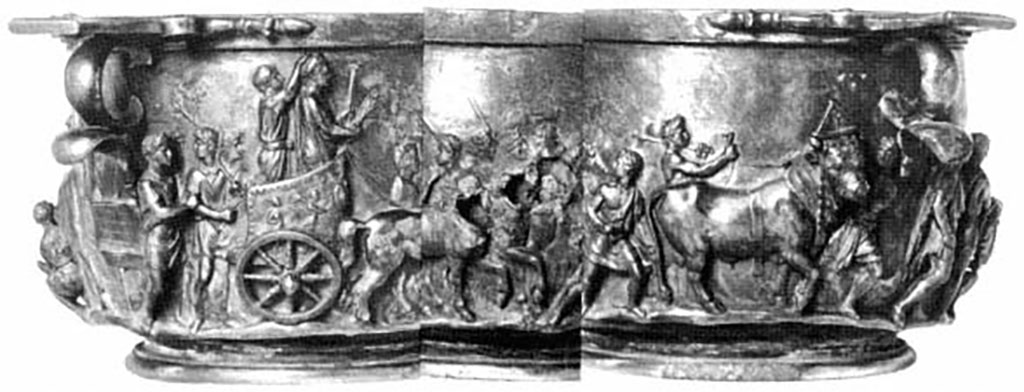

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. 1901. Silver skyphos, Augustus and the barbarians. State when found. Side 1.

According to De Villefosse in 1901 this was in the Cabinet du Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Skyphos

argenté, Auguste et les barbares. État lorsqu'il est

trouvé. Côté 1.

Selon De

Villefosse en 1901, cela a été conservé dans le cabinet du Baron Edmond de

Rothschild.

Voir/See De Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor

de Boscoreale description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XXXI.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Augustus Cup: expanded detail view of the first side when found.

According to Kuttner, the scene shows Augustus' World Rule. Mars and the provinces—Africa, Asia, Gallia, Hispania, et al, Augustus, Drusus, and the Princelings of Gallia Comata.

Skyphos,

coupe Auguste: vue détaillée élargie du premier côté

lorsqu'elle est trouvée.

Selon

Kuttner, la scène montre la règle mondiale d'Auguste. Mars et les provinces -

Afrique, Asie, Gaule, Hispanie, et al, Auguste, Drusus, et les Princelings de Gaule Comata.

See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 12, pl. 13.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Silver skyphos, Augustus and the barbarians. Current state.

Augustus receiving the submission of the barbarian peoples, including Africa wearing the remains of an elephant.

Skyphos

argenté, Auguste et les barbares. État actuel.

Auguste recevant la soumission des peuples barbares, dont l'Afrique coiffée

de la dépouille d'éléphant.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2366.

Photo (C)

RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

![Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Silver skyphos, Augustus and the barbarians.

Skyphos argenté, Auguste et les barbares.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2366.

According to Kuttner, between 1899 and 1991 no author after Héron de Villefosse seems to have viewed the cups first-hand, or made an effort to do so.[18] They dropped out of sight, and the scholarly consensus by the 1970s was that they had been mislaid by the close of the Second World War and that the Augustus cup might have been destroyed.[19] As Francois Baratte informs me, the Rothschild family believes that the cups never left family control; they did, however, pass through a period when they were vulnerable to damage. From first-hand examination of the cups, two points emerge. For some unspecified period they were stored or passed around in such a way that previous damage was exacerbated, that is, holes already torn in the relief shell widened around their edges; this is the nature of the damage on the Tiberius cup, and it conforms to the twentieth-century "legend" of that cup's continued existence. The second point is that one of the cups, the Augustus cup, fell prey to vandalism—not the complete destruction of its "legend," but active mutilation all the same. Great swathes of silver have been torn off the core on both sides of this cup, as if someone had absentmindedly peeled a label from a beer bottle; this may be accidental damage. However, in at least one place one can see that someone has cut crudely around the outlines of figures in high relief, as if to detach as a keepsake one figure at a time: such crude shear marks are clearly visible around the missing officer who stood behind Augustus, and the neat rectangular tear in front of Roma may also demonstrate such clipping.

Selon Kuttner, entre 1899 et 1991, aucun auteur après Héron de Villefosse ne semble avoir vu les coupes de première main, ni fait un effort pour le faire. Ils sont tombés hors de vue, et le consensus savant par les années 1970 était qu'ils avaient été égarés par la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et que la coupe d'Auguste aurait pu être détruite. [19] Comme m'informe François Baratte, la famille Rothschild croit que les tasses n'ont jamais quitté le contrôle de la famille; ils ont cependant traversé une période où ils étaient vulnérables aux dommages. De l'examen de première main des tasses, deux points émergent. Pendant une période indéterminée, ils ont été entreposés ou passés autour de telle manière que les dommages antérieurs ont été exacerbés, c'est-à-dire les trous déjà déchirés dans la coquille en relief e sont élargis autour de leurs bords; c'est la nature des dommages sur la coupe Tibère, et il est conforme à la «légende» du XXe siècle de l'existence continue de cette coupe. Le deuxième point c’est que l'une des tasses, la coupe Auguste, a été a proie du vandalisme, non pas la destruction complète de sa « légende », mais la mutilation active tout de même. De grandes bandes d'argent ont été arrachées du noyau des deux côtés de cette tasse, comme si quelqu'un avait distraitement épluché une étiquette d'une bouteille de bière; il peut s'agit peut-être de dommages accidentels. Cependant, dans au moins un endroit on peut voir que quelqu'un a coupé grossièrement autour des contours des figures en haut relief, comme pour se détacher comme un souvenir une figure à la fois: ces marques de cisaillement brut sont clairement visibles autour de l'officier disparu qui se tenait derrière Auguste , et la déchirure rectangulaire soignée devant les Roms peut également démontrer une telle coupure.

Voir/See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 8-9.

https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft309nb1mw&chunk.id=d0e182&toc.id=d0e182&brand=eschol](Villa_013%20Boscoreale%20Villa%20della%20Pisanella%20p4_files/image056.jpg)

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Silver skyphos, Augustus and

the barbarians.

Skyphos

argenté, Auguste et les barbares.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2366.

According to Kuttner, between 1899 and 1991 no author after Héron de Villefosse seems to have viewed the cups first-hand, or made an effort to do so.[18] They dropped out of sight, and the scholarly consensus by the 1970s was that they had been mislaid by the close of the Second World War and that the Augustus cup might have been destroyed.[19] As Francois Baratte informs me, the Rothschild family believes that the cups never left family control; they did, however, pass through a period when they were vulnerable to damage. From first-hand examination of the cups, two points emerge. For some unspecified period they were stored or passed around in such a way that previous damage was exacerbated, that is, holes already torn in the relief shell widened around their edges; this is the nature of the damage on the Tiberius cup, and it conforms to the twentieth-century "legend" of that cup's continued existence. The second point is that one of the cups, the Augustus cup, fell prey to vandalism—not the complete destruction of its "legend," but active mutilation all the same. Great swathes of silver have been torn off the core on both sides of this cup, as if someone had absentmindedly peeled a label from a beer bottle; this may be accidental damage. However, in at least one place one can see that someone has cut crudely around the outlines of figures in high relief, as if to detach as a keepsake one figure at a time: such crude shear marks are clearly visible around the missing officer who stood behind Augustus, and the neat rectangular tear in front of Roma may also demonstrate such clipping.

Selon

Kuttner, entre 1899 et 1991, aucun auteur après Héron de Villefosse ne semble

avoir vu les coupes de première main, ni fait un effort pour le faire. Ils sont

tombés hors de vue, et le consensus savant par les années 1970 était qu'ils

avaient été égarés par la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et que la coupe

d'Auguste aurait pu être détruite. [19] Comme m'informe François Baratte, la

famille Rothschild croit que les tasses n'ont jamais quitté le contrôle de la famille; ils ont cependant traversé une période où ils

étaient vulnérables aux dommages. De l'examen de première main des tasses, deux

points émergent. Pendant une période indéterminée, ils ont été entreposés ou

passés autour de telle manière que les dommages antérieurs ont été exacerbés,

c'est-à-dire les trous déjà déchirés dans la coquille en relief e sont élargis

autour de leurs bords; c'est la nature des dommages sur

la coupe Tibère, et il est conforme à la «légende» du XXe siècle de l'existence

continue de cette coupe. Le deuxième point c’est que l'une des tasses, la coupe

Auguste, a été a proie du vandalisme, non pas la

destruction complète de sa « légende », mais la mutilation active tout de même.

De grandes bandes d'argent ont été arrachées du noyau des deux côtés de cette

tasse, comme si quelqu'un avait distraitement épluché une étiquette d'une

bouteille de bière; il peut s'agit peut-être de

dommages accidentels. Cependant, dans au moins un endroit on peut voir que

quelqu'un a coupé grossièrement autour des contours des figures en haut relief,

comme pour se détacher comme un souvenir une figure à la fois:

ces marques de cisaillement brut sont clairement visibles autour de l'officier

disparu qui se tenait derrière Auguste , et la déchirure rectangulaire soignée

devant les Roms peut également démontrer une telle coupure.

Voir/See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 8-9.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. 1901. Silver skyphos, Augustus and the barbarians. State when found. Side 2.

According to De Villefosse in 1901 this was in the Cabinet du Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Skyphos

argenté, Auguste et les barbares. État lorsqu'il est trouvé. Côté 2.

Selon De

Villefosse en 1901, cela a été conservé dans le cabinet du Baron Edmond de

Rothschild.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre:

Monuments et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XXXI.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Augustus Cup: expanded detail view of the second side.

According to Kuttner, the scene shows Augustus' World Rule. Roma, Genius of the Roman People, Amor, Venus, Victoria, Augustus, Mars, Gallia, et al.

Skyphos,

coupe Auguste: vue détaillée élargie de la deuxième

côté.

Selon Kuttner,

il montre la règle mondiale d'Auguste. Roma, Génie du peuple romain, Amor, Venus, Victoria,

Auguste, Mars, Gallia, et al.

See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 12, pl. 12.

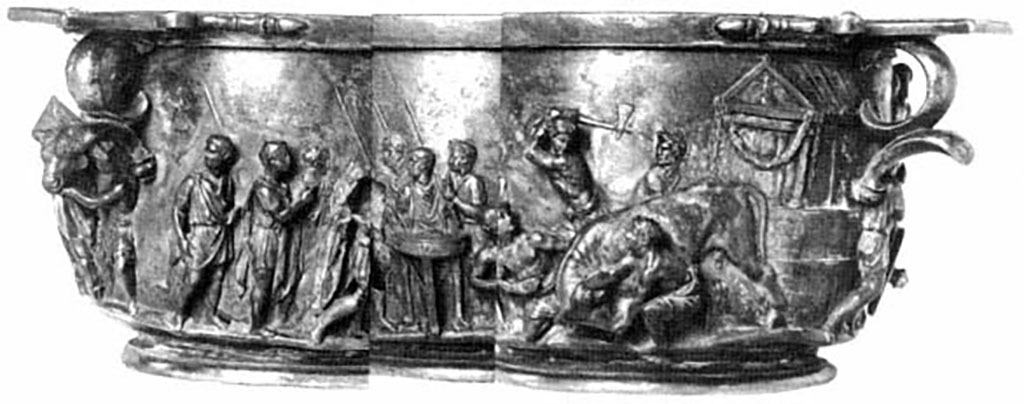

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Boscoreale Cup: Tiberius triumph

and sacrifice scene.

Skyphos, coupe

de Boscoreale : triomphe de Tibère et scène de préparation d'un sacrifice.

Now in the Louvre, inventory number BJ2367.

Photo

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della

Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Boscoreale Cup: Tiberius triumph

and sacrifice scene.

According to De Villefosse in 1901 this was in the Cabinet du Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

Skyphos, coupe

de Boscoreale : triomphe de Tibère et scène de préparation d'un sacrifice.

Selon De

Villefosse en 1901, cela a été conservé dans le cabinet du Baron Edmond de

Rothschild.

Voir/See De

Villefosse H., 1899. L’argenterie et bijoux d’or du trésor de Boscoreale

description des pièces conservées au Musée du Louvre: Monuments

et Mémoires 5 1899 avec Fascicule Supplémentaire 1902, pl. XXXVI.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Tiberius Cup: expanded detail view of one side.

The scene shows the triumph of Tiberius.

According to Kuttner, the Boscoreale Cups of Augustus and Tiberius were meant to be observed carefully and discussed knowledgeably by the owner and his friends, who would muse over details as well as over the general themes of the decoration. This particular cup pair was meant to stimulate not a literary discussion but a discussion of the historical glories and campaigns of the Augustan house; the owner must have enjoyed historical memoirs like Caesar's campaign accounts and the German wars of Pliny the Elder, as well as the poetry and philosophy relevant to the other cup pairs in his collection.

Skyphos,

coupe de Tibère: vue détaillée élargie d'un côté.

La scène

montre le triomphe de Tibère.

Selon

Kuttner, les Coupes Boscoreale d'Auguste et de Tibère étaient censées être

observées avec soin et discutées avec connaissance par le propriétaire et ses

amis, qui réfléchiraient sur les détails ainsi que sur les thèmes généraux de

la décoration. Cette paire de tasses particulière était destinée à stimuler non

pas une discussion littéraire, mais une discussion des gloires historiques et

des campagnes de la maison d’Auguste; le propriétaire

doit avoir apprécié les mémoires historiques comme les récits de campagne de

César et les guerres allemandes de Pline l'Ancien, ainsi que la poésie et la

philosophie pertinentes pour les autres paires de tasses de sa collection.

Voir/See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 12, pl. 15. https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft309nb1mw&chunk.id=d0e182&toc.id=d0e182&brand=eschol

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Skyphos, Tiberius Cup: expanded detail view of the second side.

The scene shows the sacrifice of a bull.

Skyphos, coupe de Tibère: vue détaillée élargie

de la deuxième côté.

La scène montre le sacrifice d'un taureau.

See Kuttner, Ann L. 1995. Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 12, pl. 14.

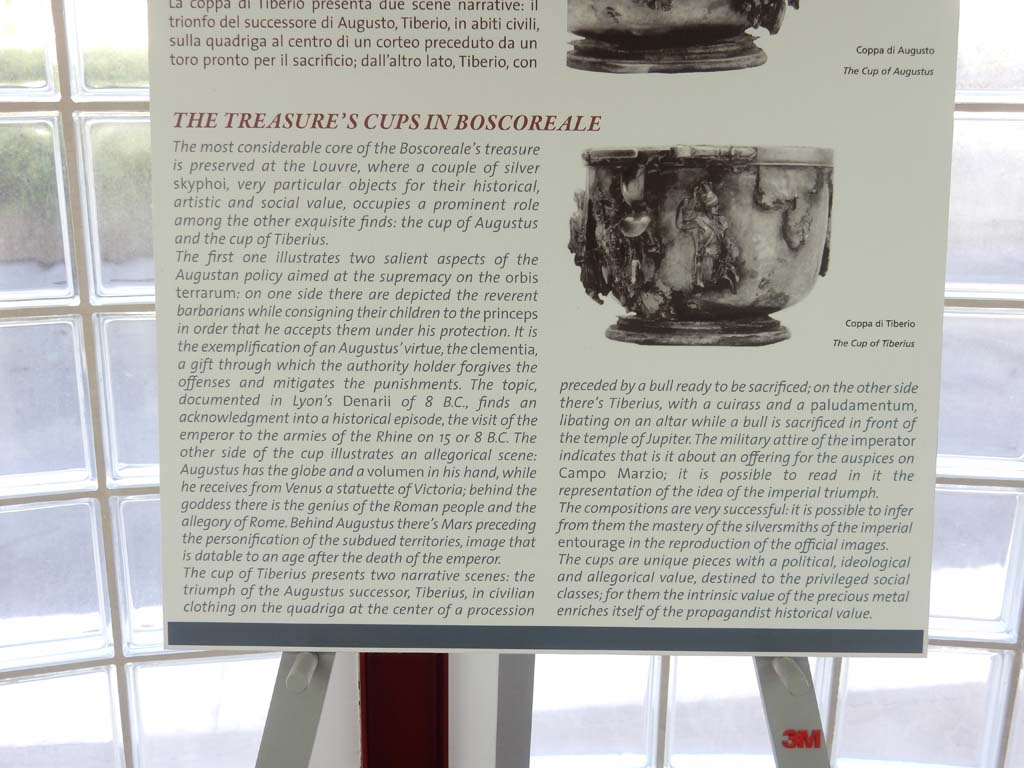

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. May 2018. Information board at Boscoreale Antiquarium with details of the cups of Augustus and Tiberius.

Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

Casale A. La favola delle

cicogne da due boccali d'argento del Tesoro di Boscoreale

https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/images/sylvamala/pdf/SYLVA%20MALA%20II%20-%201981.pdf

Per gentile

concessione di Centro Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase.

I nostri ringraziamenti ad Angelandrea Casale.

English (our

approximate translation)

Today [1981] we offer the

readers of Sylva Mala magazine a fable,

namely the ingenious interpretation of the embossed representations of two

silver mugs from the famous Silver treasure of Boscoreale (1).

The interpretation is from the

French archaeologist Héron de Villefosse who, in 1899 studied the so-called

villa of Lucio Cecilio Giocondo in Pisanella with the 128 pieces of the

treasure discovered there (2), and. donated to the Louvre in Paris by banker

Edmond de Rothschild who in turn had purchased it from the Hon. Vincenzo de

Prisco (3).

The German archaeologist Carl

Robert (1850 - 1922), one of the greatest scholars of Greek myth in the decades

between the last century and ours, in his work "Archaeologische Hermeneutik" (4) published in Berlin in 1919. de

Villefosse and illustrates it to us very simply.

The fable takes place in four

scenes (in fact there are two scenes for each silver mug) and deals with the

adventures that happened once to a couple of storks.

Here is what Carl Robert tells

us (5): The two storks have built their nest on an old tree, and the female has

hatched three young ones. However, one day when the parents had flown away in

search of food and the stork mother had preyed on a snake, they found

everything terribly turned upside down on their return. A large crab had

settled comfortably in the nest. One of the little expelled ones has taken

refuge on the top of a nearby tree, a nursery that the second tries to reach,

fluttering frightened. The third (that the little ones are three can be

obtained from the following scenes) has tried to escape even further, since we

cannot see it anywhere.

But here is the father stork,

who is lurking on another tree nearby, with a vigorous beak blow throws the

crab out of the nest. However, there is also a second enemy, who for the moment

is still calm, a third stork, of which we would not be able to guess if it is

an old esteemed relative who has been entrusted with the supervision of the

young, or an ancient and unfortunate rival in love of his father, who sees his

family happiness with resentment. This tritagonist tries to steal the snake in

the beak of a stork mother, who, angry, turns to look at him (fig. 1).

In the second scene, the mother

has rearranged the babies well in the cleaned nest and hands them the captured

snake. Two of the young greedily tend the neck towards the prey: the third

instead turns the head to the side, where the enemy stork, which has not

abandoned its positions, with the neck stretched forward and the wings

half-deployed undertakes a new assault on the snake. Meanwhile, stork father

returns from a new hunting tour with a grasshopper in his beak. A bird on the

tree on the right eagerly looks up at it (fig. 2). But the delicious morsel

also arouses the greed of the family enemy. It renounces the snake, which the

stork mother can now safely offer to her young, and, standing up and flapping

its wings, protrudes its beak towards the grasshopper, which the stork father

prevents him from grasping by turning his head. The small covetous bird has

flown to the left and resignedly witnesses the struggle between the two more

powerful than him (fig. 3).

In the fourth scene the fight

is decided. The intruder strides away, not without turning his head angrily.

Stork father delivers the prey to the female, who welcomes it by twisting her

neck backwards.

Two of the little ones follow

the beaten enemy with their eyes, while the third already stretches its neck

towards the grasshopper (fig. 4) (6). Besides the bird mentioned above, a

tortoise, a shrimp, two spiders and two rabbits act as spectators.

ANGELANDREA CASALE

(1) On Boscoreale

see: A. Casale - A. Bianco, Boscoreale e

Boscotrecase, 2° ed..

1980.

A. Casale, Boscoreale:

2000 anni dl storia, 1982.

(2) See Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, 1876, p. 196 sgg.; 1877, p. 17 sgg.; 1895,

p. 207 sgg.; 1896, p. 204 sgg. e 230 sgg.; 1899, p. 14 sgg.

Pasqui A , La villa pompeiana delle Pisanella presso Boscoreale,

In Monum. Ant. Acc, Lincei, 7, 1897, pp. 397 - 554.

De Villefosse H.. Le trésor de Boscoreale, In Monuments Ant. Piot,

V, 1899.

De Villefosse H.,

L'argenterie et les bijoux d'or du trésor de Boscoreale, Parigi, 1903.

Mau A., Ausgrabungen

von Boscoreale, in Römische Mitteilungen, 1896.

(3) On the discovery of

the silver treasure see : Corti E., Ercolano e Pompei ,Torino, 1963, pp. 218

- 220.

On the history of

the suburban excavations see:: A.

Casale, Breve storie degli scavi archeologici nel Pagus Augustus,

Pompei, 1979.

(4) Italian

Edition: Robert C., Ermeneutica Archeologica, Napoli, 1976.

German Ed.: Robert

C., 1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer

Bildwerke. Berlin.

(5) Italian Edition: Robert C., op. cii., pp. 184 - 185.

German Ed.: Robert C., 1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 97-100.

(6) Italian Edition: Robert C., op. cii., figg. 80 - 83, pp. 186 - 187.

German Ed.: Robert C., 1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung

klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 98-99, figg. 80-83.

See

Casale A. La favola delle cicogne da due boccali d'argento del Tesoro di

Boscoreale: Sylva Mala II 1981, p. 5.

https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/images/sylvamala/pdf/SYLVA%20MALA%20II%20-%201981.pdf

Courtesy of

Centre for Archaeological Studies of Boscoreale, Boscotrecase and Trecase. Our thanks to Angelandrea Casale.

Italiano

Oggi [1981] proponiamo

ai lettori della rivista Sylva Mala una favola, ovvero la ingegnosa

interpretazione delle raffigurazioni a sbalzo di due boccali d'argento

provenienti dal famoso Tesoro di argenterie di Boscoreale (1)

.

L'Interpretazione

è dovuta all'archeologo francese Héron de Villefosse che, nel 1899 studiò la

villa cosiddetta di Lucio Cecilio Giocondo alla Pisanella con I 128 pezzi del

tesoro ivi scoperto (2), e. donato al Louvre di Parigi dal banchiere Edmond de

Rothschild che a sua volta lo aveva acquistato dall'On. Vincenzo de Prisco (3).

L'archeologo

tedesco Carl Robert (1850 - 1922), uno del più grandi studiosi del mito greco

nei decenni fra il secolo scorso ed il nostro, nella sua opera “Archaeologlsche Hermeneutik” (4)

pubblicata a Berlino nel 1919. riprende l'interpretazione del de Villefosse e

ce la illustra con molta semplicità.

La favola si

svolge in quattro scene (Infatti sono due le scene per ogni boccale d'argento)

e tratta delle avventure capitate una volta ad una coppia di cicogne.

Ecco quanto ci

dice Carl Robert (5): Le due cicogne hanno costruito il loro nido su di un

vecchio albero, e la femmina ha covato tre piccoli. Tuttavia, un giorno che I

genitori erano volati via In cerca di cibo e madre cicogna aveva predato un

serpente, trovarono al ritorno tutto terribilmente a soqquadro. Un grosso

granchio si era comodamente sistemato nel nido. Uno dei piccoli scacciati si è

rifugiato sulla cima di un albero vicino, asilo che anche il secondo tenta di

raggiungere svolazzando impaurito. Il terzo (che i piccoli siano tre lo si

ricava dalle scene seguenti) ha cercato scampo ancor più lontano, poiché non

riusciamo a scorgerlo da nessuna parte.

Ma ecco che

padre cicogna, appostatosi su un altro albero vicino, con un vigoroso colpo di

becco scaraventa il granchio fuori dal nido. E'

presente però anche un secondo nemico, che per il momento se ne sta ancora

tranquillo, una terza cicogna, di cui non sapremmo indovinare se si tratti di

un vecchio parente d'acquisto al quale sia stata affidata la sorveglianza dei piccoli,

o di un antico e sfortunato rivale in amore del padre, il quale veda con astio

la sua felicità familiare. Questo tritagonista tenta di carpire il serpente nel

becco di madre cicogna, che incollerita si volta a guardarlo (fig. 1) .

Nella seconda scena la madre ha risistemato ben bene i piccoli nel nido

ripulito e porge loro il serpente catturato. Due dei piccoli tendono

golosamente il collo verso la preda: il terzo invece gira Il capo di lato, dove

la cicogna nemica, che non ha abbandonato le sue posizioni, col collo teso in

avanti ed ali mezzo dispiegate intraprende un nuovo assalto al serpente. Nel

frattempo, padre cicogna torna da un nuovo giro di caccia con una cavalletta

nel becco. Un uccellino sull'albero a destra leva voglioso lo sguardo su di

essa (fig. 2) . Ma il prelibato bocconcino suscita anche l'avidità del nemico di famiglia.

Esso rinuncia al serpente, che madre cicogna può ormai tranquillamente offrire

in pasto ai suoi piccoli, ed ergendosi e dibattendo le ali protende il becco

verso la cavalletta, che padre cicogna gli impedisce di afferrare voltando la

testa. Il piccolo uccello bramoso è volato sulla sinistra ed assiste rassegnato

alla lotta fra I due più potenti di lui (fig. 3).

Nella quarta

scena la lotta è decisa. L’intruso si allontana a gran passi, non senza volgere

irosamente il capo. Padre cicogna consegna la preda alla femmina, che

l'accoglie torcendo Il collo all'indietro.

Due dei piccoli

seguono con lo sguardo Il nemico battuto, mentre il terzo già allunga il collo

verso la cavalletta (fig. 4) (6). Fungono da spettatori, oltre l’uccellino già

menzionato, una tartaruga, un gambero, due ragni e due conigli.

ANGELANDREA

CASALE

(1) Su Boscoreale

vedi: A. Casale - A. Bianco, Boscoreale e Boscotrecase, 2° ed.. 1980.

A. Casale, Boscoreale:

2000 anni dl storia, 1982.

(2) Not. Scavi,

1876, p. 196 sgg.; 1877, p. 17 sgg.; 1895, p. 207 sgg.; 1896, p. 204 sgg. e 230

sgg.; 1899, p. 14 sgg.

Pasqui A , La villa pompeiana delle Pisanella presso Boscoreale,

In Monum. Ant. Acc, Lincei, 7, 1897, pp.

397 - 554.

De Villefosse H.. Le trésor de Boscoreale, In Monuments Ant. Piot,

V, 1899.

De Villefosse H.,

L'argenterie et les bijoux d'or du trésor de Boscoreale, Parigi, 1903.

Mau A., Ausgrabungen

von Boscoreale, in Römische Mitteilungen, 1896.

(3) Sul

rinvenimento del tesoro d'argenterie vedi : Corti E., Ercolano

e Pompei ,Torino, 1963, pp. 218 - 220.

Sulla storia

degli scavi nel suburbio vedi : A. Casale, Breve

storie degli scavi archeologici nel Pagus Augustus, Pompei, 1979.

(4) Ediz. italiana:

Robert C., Ermeneutica Archeologica, Napoli, 1976.

Ediz. Tedesco:

Robert C., 1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung

klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin.

(5) Robert C.,

op. cii., pp. 184 - 185.

Ediz. Tedesco:

Robert C., 1919. Archaeologische

Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 97-100.

(6) Robert C.,

op. cii., figg. 80 - 83, pp. 186 - 187.

Ediz. Tedesco: Robert

C., 1919. Archaeologische

Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 98-99, figg. 80-83.

Vedi Casale A. La

favola delle cicogne da due boccali d'argento del Tesoro di Boscoreale:

Sylva Mala II 1981, p. 5.

https://centrostudiarc.altervista.org/images/sylvamala/pdf/SYLVA%20MALA%20II%20-%201981.pdf

Per gentile

concessione di Centro Studi Archeologici di Boscoreale, Boscotrecase e Trecase.

I nostri ringraziamenti ad Angelandrea Casale.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Paris, Louvre.

Silver cups from the treasure of Boscoreale, 1st cup, sides A and B.

Parigi, Louvre. Boccali d’argento dal tesoro di

Boscoreale, 1° boccale, lato A e B.

See Robert C., 1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 98-99, figg. 80-81.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Paris,

Louvre. Silver cups from the treasure of Boscoreale, 2nd cup, sides A and B.

Parigi, Louvre. Boccali d’argento dal tesoro di

Boscoreale, 2° boccale, lato A e B.

See Casale A. La

favola delle cicogne da due boccali d'argento del Tesoro di Boscoreale:

Sylva Mala II 1981, p. 5, fig 3-4.

See Robert C.,

1919. Archaeologische Hermeneutik; Anleitung zur Deutung klassischer

Bildwerke. Berlin. Pp. 98-99, figg. 82-83.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Pair of cantharus, scenes with cranes. Side A.

Paire de

canthares, scènes avec des grues. Côté A.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1905 and BJ1906.

Photo (C)

RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Pair of cantharus, scenes with cranes. Side B.

Paire de

canthares, scènes avec des grues. Côté B.

Now in the Louvre, inventory numbers BJ1905 and BJ1906.

Photo (C)

RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale. Pair of silver cups with cranes in relief.

According to the Morgan Library, each cup consists of an inner liner and an outer casing, which is worked in repoussé.

The original silver gilt has largely worn away, and the double handles are missing.

There are guide marks for placing of handles in Greek letters.

The decoration consists of cranes feeding among wheat or sorghum, hunting snakes, a lizard, butterflies, and a grasshopper.

On one side of one cup, the birds stand beside poppies.

Although the cups were found in Rome, they are believed to be the work of a

Greek craftsman.

Probably from the Villa Maxima [=Villa Pisanella] at Boscoreale.

See https://www.themorgan.org/objects/item/161025

Now in The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Purchased by J.P. Morgan, inventory number AZ050-1 and AZ050-2.

Villa della Pisanella, Boscoreale? Stemless silver cup engraved with floral designs and with a gold pin in the centre.

The cup was purchased by the museum from V. Vitalini in 1897.

The bronze Scylla dish (inventory number BM 1897,0726.7) found in Villa Pisanella was also acquired from V. Vitalini in 1897.

Both items are shown simply on the BM website as Boscoreale. Is this silver cup also from Villa Pisanella?

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum, inventory number BM 1897,0726.1. Use subject to CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.