54. Torre Annunziata, Villa di C. Siculius

or Siculus, masseria Scognamiglio.

Excavated 1841.

Villa of C. Siculus or Siculius found in the Masseria di Pasquale Scognamiglio, at Torre Annunziata, during the digging of the trench for construction of Portici to Castellammare railway, in December 1841.

Bibliography

Casale, A.,

Bianco, A., Primo contributo alla

topografia del suburbio pompeiano: Supplemento al n. 15 di ANTIQUA

ottobre-dicembre 1979, 119, p. 47.

Clarke, John R. 2014. Oplontis: Villa A ("of Poppaea") at Torre Annunziata, Italy. New York: American Council of Learned Societies. Chapter 3 [paras. 236-245] web version

Corcia, N., 1845.

Storia delle Due Sicilie. Napoli.

Della Corte, M.,

1965. Case ed Abitanti di Pompei. Napoli: Fausto Fiorentino, p. 450.

Garcia y Garcia,

L., 2017. Scavi Privati nel Territorio di

Pompei. Roma: Arbor Sapientiae, No. 7, p. 64-72.

Malandrino, C.,

1977. Oplontis, Napoli, pp. 51-53 and

fig. 9, n. 3.

Marasco, V. 2014. A Historical Account of Archaeological Discoveries in the Region of Torre Annunziata, in Oplontis Project eBook: Chapter 3 English edition

Marasco, V. 2014. La storia delle scoperte archeologiche

nella zona di Torre Annunziata. Oplontis Project eBook:

Capitolo 3 Edizioni Italiana

Ruggiero, M., 1888. Degli scavi di antichità nelle province di terraferma dell'antico regno di Napoli dal 1743 al 1876. Napoli: V. Morano, p. 104ff.

Van der Poel, H. B., 1981. Corpus Topographicum Pompeianum, Part V. Austin: University of Texas, n. 54, p. 22 and plan.

Zahn, W., 1852-59.

Die schönsten Ornamente und merkwürdigsten Gemälde aus Pompeji, Herkulanum

und Stabiae: III. Berlin: Reimer, taf. 65.

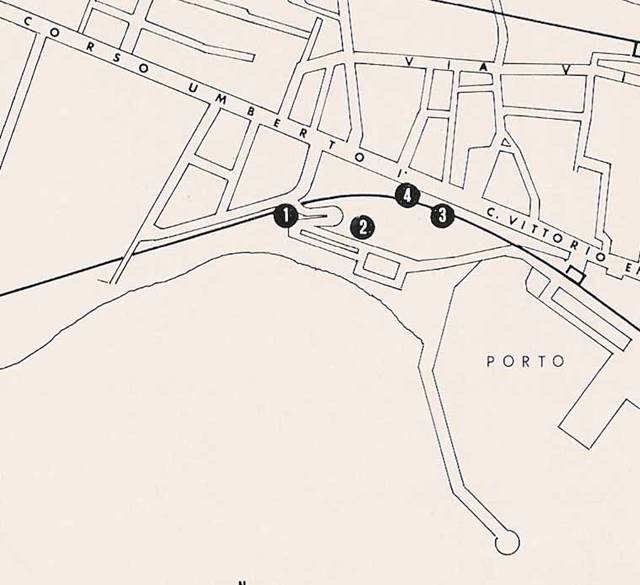

Villa 54. Torre

Annunziata, Location plan.

1: The Baths of Marco Crasso Frugi.

2: Villa 89.

3: Villa 54 The Villa of C. Siculius.

4: Remains uncovered in 1940 and reburied without further investigation (Casale Bianco 141).

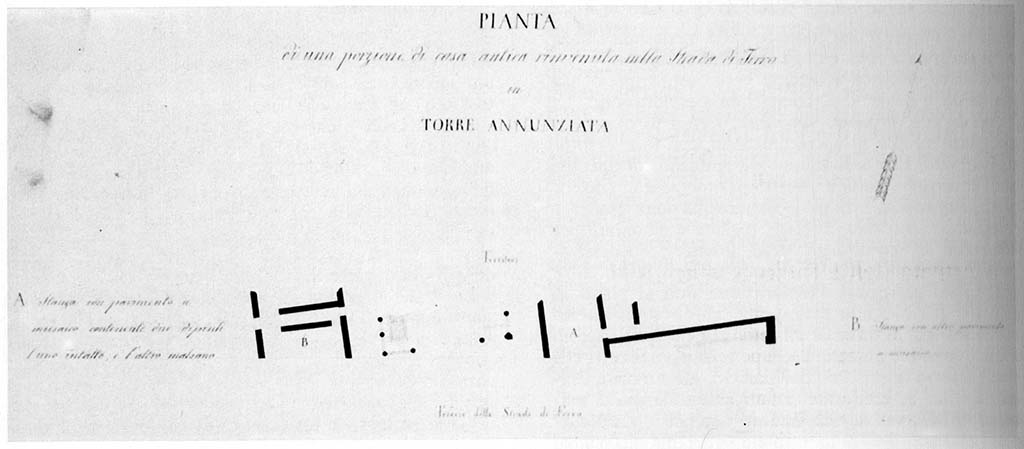

54. Torre Annunziata, Villa di C. Siculius or Siculus. Pianta di una porzione di casa antica

rinvenuti nella Strada di Ferro in Torre Annunziata, firmata da G. Cirillo

(1842).

Ora a Napoli, Museo di Capodimonte.

Plan of a portion of an ancient house found on the railway line in Torre Annunziata, signed by G. Cirillo (1842).

Now in Naples, Capodimonte Museum.

See Pagano, M., Torre

Annunziata. Planimetrie borboniche della villa A e di quella di C. Siculius.

Rivista di Studi Pompeiani V, 1991-2, p. 219-221.

Description by Carlo Malandrino

According to Malandrino, approximately 500m from the Baths of Frugi, in the Masseria of Pasquale Scognamiglio, now [1977] held by the Suore di Cristo Re, just before the gate by which you enter Torre Annunziata, specifically mentioned by Corcia (near the place called Stallone, where, during the Bourbon period, there were the royal stables), during excavation for the railway line Portici-Castellamare-Nocera were found the remains of an important roman villa.

According to details published by Ruggiero the walls of several rooms with painted walls, mosaic floors, furnishings and various objects, some decorated with silver, a table with black granite top broken into nine pieces and feet with a joined base, worked with cornice and foliage, as well as a putto, two groups and a marble basin. In one of these groups can be recognised the faun and small panther mentioned by Corcia.

The paintings, one of Narcissus, and the floors were cut out and, together with all the objects were sent to the Museo Nazionale, other than those that Avellino’s report had described as “disperse in vari mani”.

In the course of the excavations a bronze ring seal was found that showed, very probably, the name of the villa owner C. SICVLI C. F. [Marasca expands this as Caius Siculius Caius Filius (Gaius Siculius, son of Gaius)]

Of all these findings, now, other than the diligent and valuable reports of Ruggiero, there is no other record, nor was there time to conduct more accurate studies especially because the economic interests of sig. Bayard, the railway concessionaire, conflicted with the interests of archaeology and, as almost always happens, the former won.

An ancient manuscript of the 18th century refers to the area as Monte Parnaso, which may date from Roman times. Parnaso or Parnassus indicated a sacred place where the Dionysian cults were celebrated. The cult was strictly forbidden by the senate (Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus) but was still popular in Campania where there were vast vineyards “under the protection of Bacchus” and was generally practiced in suburban villas and perhaps the Villa of C. Siculi. The truth is perhaps contained in the depths of the cliff, which, on balance, should still preserve much of the villa.

See Malandrino, C., 1977. Oplontis, Napoli, pp. 51-53 and fig. 9, n. 3.

See Ruggiero, M., 1888. Degli scavi di antichità nelle province di terraferma dell'antico regno di Napoli dal 1743 al 1876. Napoli: V. Morano, p. 104ff.

See Corcia N., 1845. Storia delle Due Sicilie. Napoli.

A Historical Account of Archaeological Discoveries in the Region of Torre Annunziata by Vincenzo Marasco

March 1841–April 1843: Construction of the “Bayard” railroad

A project that sparked great interest in

the whole kingdom was construction of the section of railroad to link Naples

and Nocera Inferiore, with a branch from Torre Annunziata to Castellammare di

Stabia. This large project was planned and undertaken by the engineer Armando

Giuseppe Bayard de la Vingtrie. King Ferdinand II

signed the contracts on 19 June 1836. This first section of track from Naples

to nearby Portici was opened to the public on 4 October 1839. The second

section from Portici to Torre del Greco was inaugurated in 1840. The

construction of the third leg of the railway, which included the connection

between Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata, began in March 1841.

During the excavation of the cliff face,

which is a typical feature of the coast between Torre del Greco and Torre

Annunziata, many important archaeological remains emerged, starting at Torre

del Greco. Francesco Maria Avellino, director of the Royal Museum and general

superintendent of excavations of the Kingdom, as soon as he heard about what

was taking place in the excavation at Torre del Greco near the area of Sora,

rushed to the site but could only confirm the havoc that had been wrought.

Beyond the various buildings with fine decorations and modest mosaics uncovered

during that excavation, remains were found of an important Roman building known

as the Villa Giulia Imperatoria, mentioned by Seneca.

Because of the discoveries in Torre del

Greco, the Superintendency of Antiquities had to appoint an inspector to

supervise the excavations and save any future finds. Soon after the excavation

trench passed the newly restored Terme Nunziante, near the area known as

Stallone on the Scognamiglio property (today the Istituto Cristo Re), another

problematic find attracted the attention of Avellino. Between the lines of

Avellino's report, the architect Pietro Bianchi of the nearby Pompeii

excavations inserted these comments in a note of 22 December 1841:

…continuandosi il lavoro della strada di

ferro nel sito della masseria di D. Pasquale Scognamiglio, nel tenimento di

Torre Annunziata, nel ribassamento di circa palmi dodici si sono palesate

alcune pareti di un'antica abitazione e da esse si sono staccati varii pezzi d'intonaco similissimi a’

pompeiani, i quali si sono dispersi in varie mani…

… proceeding with the work on the railway

at the site of the farm of Don Pasquale Scognamiglio, in the territory of Torre

Annunziata, at a depth of about 12 palms, some walls of an ancient dwelling

appeared and from them some pieces of plaster, very similar to the types in

Pompeii, came off and were dispersed among various hands….

At this point the problem became clear: None of the regulations put into place to protect antiquities found during the railway excavations was being respected.

Plans of Gabriele Cirillo

Considering the economic interests in play for the realization of the railway project, all the necessary drawings had to be made as quickly as possible in order at least to understand the importance of the discoveries. The mayor of Torre Annunziata, the person charged with the safety of this patrimony, was asked to allow an expert from the Superintendency, the architect Gabriele Cirillo, to make the required drawings. The first thing Cirillo did when he arrived at the excavations was to make an accurate plan of all the works uncovered so far. On the basis of this plan, it is possible to establish the real features and elegance of the newly discovered building (see FIG. 3.11 link below).

Report of Francesco Maria Avellino,

29 January 1842

On 29 January 1842, having inspected the

site of the excavations, Avellino reported the following to the Ministry of

Internal Affairs:

Finally, I was able, last Thursday

morning, to satisfy the desire I have had for a long time to visit the walls

discovered during the excavations for the railway in the site on the

Scognamiglio farm at Torre Annunziata. I therefore resigned myself to the fact

that the major paintings that were on those walls, and that were drawn by Sig.

Abate, have been removed … in the actual state nothing more of importance is

left, in truth only a few elegant paintings and arabesques of the type that are

abundant all over the place in Pompeii. However, it seems to me that Your

Excellency's attention should be drawn to the following objects. In the aforementioned

excavation there is a black-and-white mosaic pavement about 24 palms wide with

a length that I could not determine from my high vantage point. It appears to

be in good condition in its middle section and could, as is usually the case,

be adorned with elegant decorations. It thus seems appropriate to expose it and

take it to the museum, if you are able to do this.

Part of the floor has not been uncovered

yet, so it is not possible to know if there are other mosaics, and one portion

of the walls that could have more paintings has not yet been uncovered. I

therefore propose that a complete excavation be undertaken as quickly as

possible, using state-of-the-art methods and under the direction of the

Superintendency, of all the ancient remains including the section of railway

already opened; that a plan and full description be completed; that any other

paintings that might appear be saved and that we proceed in the most

workmanlike manner to extract and move to Naples the aforementioned mosaic as

well as any other worthy mosaics that may emerge. Finally, any objects that

might be found must be preserved for study as has been done with those found so

far…. Finally, other than the painting that was detached, I need to deliver to

Your Excellency the various objects found so far in the excavation in question

consisting of some harpoons and other bronze tools, among them a round inkwell;

a lead plate without letters or images; some lamps; some pieces of fallen

plaster with arabesques; a coin in bad condition of the emperor Commodus; a

broken and fragmentary naturalistic arm in marble. It is my opinion that this

painting that has been excavated should be taken immediately to the Royal

Museum; that the arm should remain on the site in the custody of Paribelli in the

hope that the rest of the statue is found; that all the other objects can be

given to the owner without inconveniencing anyone… Avellino (min). [in Italiano]

Coin from the era of Emperor Commodus

One of the finds that continues to inspire

debate is the coin from the era of Commodus. (Marcus

Aurelius Commodus Antoninus, as Commodus was Emperor from

180 to 192 AD.) The find further

endorses the hypothesis that this part of the coast was reinhabited after the

eruption of A.D. 79.

There were numerous interesting finds in

this building. Other than the fine wall paintings and floor mosaics that were

removed and taken to the Royal Bourbon Museum, there were many objects of

various types of material and nature in the rooms, described in minute detail

in the excavation reports of Gioacchino Paribelli. [in Italiano] Among the terracotta fragments found was

an amphora neck with handles still attached that had the Greek inscription ϕιλιππoς καισαρ [in Italiano]

Find reports of Gioacchino

Paribelli

“Torre Annunziata, 20 January 1842.… on Tuesday of this month the following objects were found in those excavations, that is, bronzes, a scale with a plate missing, an inkwell with its lid, half a hinge. … Gioacchino Paribelli.

5 February 1842 …in front of the Ministry of the Interior, from inside the railway to Torre Annunziata we found…. three sheets of lead… with an inscription in the same attached to the lead at about the thirtieth roll; …a piece of lead thought to be a gasket…Paribelli

Torre Annunziata Railway, 18 February 1842. On Monday February 14, at 13.00 hours D. Raffaele and D. Luigi Piedimonte came to remove the mosaics that were found on the floors; meanwhile at 17.00 hours the following objects were found; that is, in bronze, a dish …with only a small broken handle on the lip; a vase in the form of a cauldron …with missing handles and broken on one side, a small coin, half a hinge. Iron: a type of hook, a small foot in the shape of an animal. Terracotta: four amphorae, two sieves…. Paribelli

20 February 1842 … eight more pieces of mosaic found in the Torre Annunziata railway were taken to the Royal Museum. …Dell'Aquila.

… the railway, 5 March 1842. During February and during this week of March, twenty pieces of mosaic were removed …, that is, twelve black-and-white mosaics and eight black ones. On March first, a small room with white mosaics was found, from this room were removed… fresco paintings of two little Putti and another small one representing a mullet. Paribelli.

18 March 1842. In the Torre Annunziata railway: bronze, a door hinge, also, a piece of iron with silver trim, broken on one side; lead, lengths of pipe belonging to some fountain. Paribelli.

15 April 1842. In the Torre Annunziata railway a bronze key and a piece of lead… perhaps belonging to a fountain, were found.… Paribelli.

28 May 1842. In the Torre Annunziata railway were found: bronze, two scales missing their plates. Also, a piece of iron. Also, a room with mosaics … with a black mosaic band around it. Paribelli.

17 June 1842, In the Torre Annunziata railway: bronze: seventeen little coins, a door hinge and a piece of wood were found. Paribelli.

Torre Annunziata, 15 November 1842. In laying out the second track in the area of Torre Annunziata, … the remains of five rooms appeared, and there was found a terracotta lamp decorated with low relief. … Paribelli.

21 November 1842. In the section of the Torre Annunziata

railway, a bronze padlock was found, and three brick columns decorated with

stripes and belonging to a colonnade … a portion of the structure of those five

rooms fell to the ground because they were excavating at night. …Paribelli.

Torre Annunziata,

24 November 1842. Bronze: a spool and a terracotta bird-drinking trough. …

Paribelli.

Torre Annunz. 25 November 1842. In the railway… in my presence, the following objects were collected. Bronze: two similar vases … an oblong basin in fragments … another small vase … with only one handle. Two small hinges. Two small furniture handles. Iron. A clamp. … Paribelli.

In the railway of Torre Annunziata on 30 November 1842. A plate for a hand-held scale, un mezzo ricchetto [editors' note: probably rocchetto, “spool”] and six coral beads, iron … half a room was discovered with a white mosaic floor with two black bands …the buildings had all fallen to the ground. … Paribelli.

7 December 1842. A bronze coin and seven pieces of lead pipe…Paribelli.

21 December 1842. This week a black mosaic pavement surrounded by a white band was discovered … the buildings had fallen and could no longer be found.… Paribelli.

10 June 1843. Two small bronze handles belonging to a vase. Two nails, also of bronze. Paribelli.

Torre Annunziata, 20 January 1843. Yesterday at 19.00 hours Italian time, from excavations undertaken in the second line of the Torre Annunziata railway, a black granite slab broken into nine pieces was found, also, a white marble base with iron-lead feet decorated with bronze was excavated, … the bases were decorated with frames and foliage.… Paribelli.

Torre Annunziata, 28 January 1843, at 22 hours Italian time, a bronze seal was found with the following letters inscribed on its edges. Paribelli. C·SICVLI·C·F.

Torre Annunziata, 10 February 1843. A small squared pier of

white marble with a frame around it was found. …Paribelli.”

See Ruggiero, M., 1888. Degli scavi di antichità nelle province di terraferma dell'antico regno di Napoli dal 1743 al 1876. Napoli: V. Morano, pp. 104-109.

Bronze seal

One of the most important finds on the site was a bronze seal in the form of a ring inscribed with the name of the probable dominus, or owner of the building.

In his regular report to superintendent Avellino, the custodian Paribelli described the find:

Torre Annunziata, 28 January 1843, at 22 hours Italian time, a bronze seal was found with the following letters inscribed on its edges. Paribelli. C·SICVLI·C·F. [CIL X 8058, 80]

As Ruggiero indicates, the inscription establishes that the building belonged to a certain Caius Siculius Caius Filius (Gaius Siculius, son of Gaius).

“Nei 28 Gennaio

1843 alle ore

22 d'Italia si e rinvenuto un sigillo di bronzo che

imprime le seguenti lettere che trovate in margine. Paribelli. C · SICVLI · C ·

F (C.I. L. n. X 8058, so. Mus. naz.

no. 4761) “

See Ruggiero, M., 1888. Degli scavi di antichità nelle province di terraferma dell'antico regno di Napoli dal 1743 al 1876. Napoli: V. Morano, p. 108.

Torre Annunziata, Villa of C. Siculius. Bronze seal of C Siculi C F.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 4761.

Photo: V. Marasco. Oplontis Project e-book (FIG. 3.13a). See https://hdl.handle.net/2027/fulcrum.8049g5702

Torre Annunziata, Villa of C. Siculius. Ring of bronze seal of C Siculi C F.

On the back of the ring is an interesting reference in the form of a relief of a small ovoid form, narrowed and tapered at the top, representing perhaps a bottle or similar container.

The presence of this detail suggests that the owner could be a merchant.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 4761.

Photo: V. Marasco. Oplontis Project e-book (FIG. 3.13b). See https://hdl.handle.net/2027/fulcrum.xk81jm23v

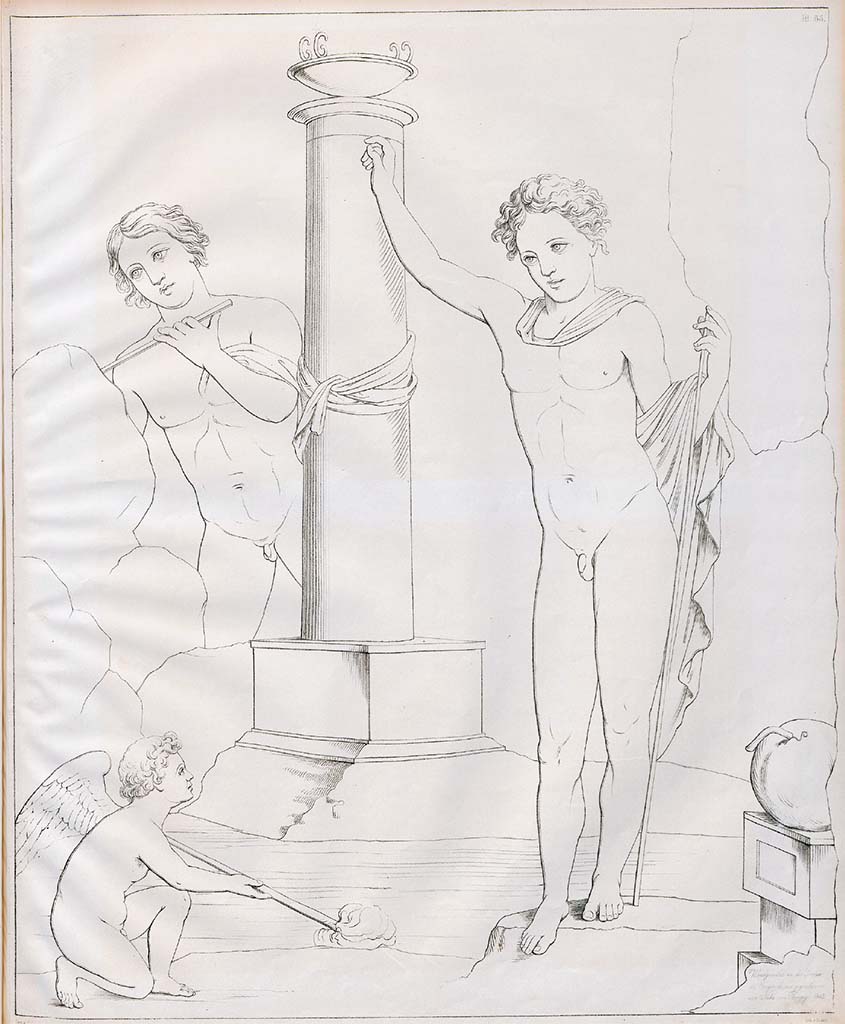

Painting of the Death of Narcissus.

Torre Annunziata, Villa of C. Siculius. Painting of Narcissus and Echo.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 9385.

Photo: V. Marasco. Oplontis Project e-book (FIG. 3.12). See https://hdl.handle.net/2027/fulcrum.rx913q67x

According to Malandrino, this was found in this villa.

According to Marasco, “During the brief exploration of the building, a fresco depicting the myth of Narcissus and Eco was detached from the walls of one of the rooms brought to light. More detailed information about this find comes from a report written a few years later by Giulio Minervini published in Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano”.

According to Pagano, this was found in this villa and is noted on the 1842 plan signed by the architect G. Cirillo, and its execution is recorded also in the documentation of the archives.

See Pagano M.,

1991-2. Torre Annunziata: Planimetrie

borboniche della villa A e di quella di C. Siculius: Rivista di Studi

Pompeiani V, p. 219-220, fig. 26 and note 3.

According to Minervini, in the detailed report about this find published in the Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano “now we want bring to the attention of our readers a wonderful painting that was also found during those excavations that presents us with a subject that is new in archaeology, the myth of Echo associated with the more common subject, especially in Pompeii, of the sad death of Narcissus. This beautiful painting was found in the excavations that were undertaken in the property of Sig. Scognamiglio at a site by the sea before the gate through which one enters Torre Annunziata. In that place was a partially discovered villa whose remains suggest great luxury. Large, highly decorated rooms were not lacking, done with the taste and style found in Pompeii, although they were to a large extent either fallen or collapsing. The beautiful rectangular painting of which we speak was detached from one of these walls and taken to the Royal Museum”.

The unfortunate Narcissus is depicted standing next to a column, its funerary significance manifested by the ribbon that binds it and no less by the urn that sits on top of it. He is intent on admiring himself in the stream that runs at his feet. To his left, along the lower edge of the painting is a little stand supporting an overturned, three-handled jar. His pose, leaning heavily upon the column with his right hand seems to point to the fact that soon the goddesses will find his tomb there. On the other side of the stele, among the stones and protruding rocks can be seen the face and bust of a nude woman with bristling and unkempt hair and a sad expression on her face. Echo turns her glance, both desirous and furtive, towards Narcissus, all the while bending delicately as if to spy on him she is the act of pressing her lips to a tibia or a transverse flute. In the foreground beneath Echo, is a Cupid who raises his eyes sadly toward Narcissus as he kneels on his right knee. He is about to extinguish his torch in the same waters in which Narcissus is admiring himself.

See Minervini G. Descrizione di un antico dipinto scoverto non lungi da Pompei, e che rappresenta il mito di

Narcisso e di Eco: Bullettino Archeologico Napoletano 40: no. 5 (1 February

1845): p. 33–34.

Torre Annunziata, Villa of C. Siculius. Drawing by Zahn of painting of Narcissus.

Zahn explains that the painting has suffered a great deal so that doubts arise about some of the details.

He shows the figure at the rear as male, perhaps Ameinias or a mountain god. He also shows the vase at the bottom right as a large gourd.

He also says that if the figure at the rear were female it would clearly be the nymph Echo.

It was excavated during the construction of the railway near Pompeii, under Torre dell' Annunziata in 1842.

See Zahn, W., 1852-59. Die schönsten Ornamente

und merkwürdigsten Gemälde aus Pompeji, Herkulanum und Stabiae: III.

Berlin: Reimer, taf. 65.

End of excavations

On 20 April of the same year the stretch of railway between Torre del Greco and Torre Annunziata was completed, which ended any news of archaeological finds connected with construction of the railway.

Reference

See Marasco V., 2014. A Historical Account of Archaeological Discoveries in the Region of Torre Annunziata, in Oplontis Project eBook: Chapter 3 English edition

See Marasco V., 2014. La storia delle scoperte archeologiche nella zona di Torre Annunziata. Oplontis Project eBook: Capitolo 3 Edizioni Italiana

Other photos

See photos referred to above, on Clarke and Muntasser Oplontis eBook 2014, using links below.

Note: Reproduction of any and all images illustrating this book requires express permission from the owners of those images. Copyright and Permissions eBook photos

FIG 3.11 Plan of part of an ancient house found during the railway project.

See M. Pagano, “Torre

Annunziata. Planimetrie borboniche

della villa A e di quella di C. Siculius,” Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 5

(1991–1992): p. 219–220.

FIG. 3.13A Bronze seal, detail of stamp of C. Siculi C. F. (MANN inv. 4761).

Photo: V. Marasco.

FIG. 3.13B Bronze seal, detail of ring part with symbol that resembles a jug or a container for liquids (MANN inv. 4761).

Photo: V. Marasco.

FIG. 3.12 Narcissus and Echo, detail of wall painting from part of ancient house found during the railway project (MANN inv. 9385).

Photo: V. Marasco.